90 Years Since “Black Sunday,” The Storm That Named the Dust Bowl

Published: April 30th, 2025

Ninety years ago on April 14th, 1935, a cold front swept across the bone-dry Great Plains, stirring the earth into the sky. What began as a breezy spring afternoon quickly transformed into a suffocating nightmare. A wall of dust estimated to be 500-600 feet high blotted out the sun, choked out the air, and left behind a devastated region and period of American history that, by the following day, became known as the Dust Bowl (1). This infamous day was Black Sunday, when a cataclysmic dust storm became a symbol of what happens when land, climate, and human activity fall out of sync.

The Dust Bowl Era

George Everett Marsh Jr. - original upload 7 March 2005, Public Domain

For thousands of years, deep-rooted native Buffalo grasses blanketed the Plains. They anchored the soil through dry spells, buffered it against the wind, and cycled nutrients through ecosystems that had evolved in stride with wildfire, bison, and climate variability. But in the 20th century, that balance was undone. Encouraged by federal land policies, expanding railroad infrastructure, and rising wheat prices during World War I, farmers swarmed into the region, replacing millions of acres of native grasslands with single-crop wheat farms. For a while they were prosperous, but the Plains is no stranger to drought.

When the rains stopped coming in the early 1930s, the region’s fragile, man-made landscape fell apart. Crops failed, topsoil dried into dust, and the wind carried on across the landscape as always. However, now there was nothing left to anchor the soil in place when the winds came. From 1930-1940, dust storms rolled across the central U.S. with troubling regularity, and entire towns were nearly buried on the inside and the out: the pervasive dust routinely sifted into homes through the tiniest cracks, people coughed through damp rags tied across their faces, and cattle suffocated in the fields as dust turned to thick mud on their snouts. Some called them “black blizzards,” others “dirt storms,” or “dusters” (1). No matter what people called them, these formidable storms all brought with them the same relentless, inescapable taste of earth.

Black Sunday

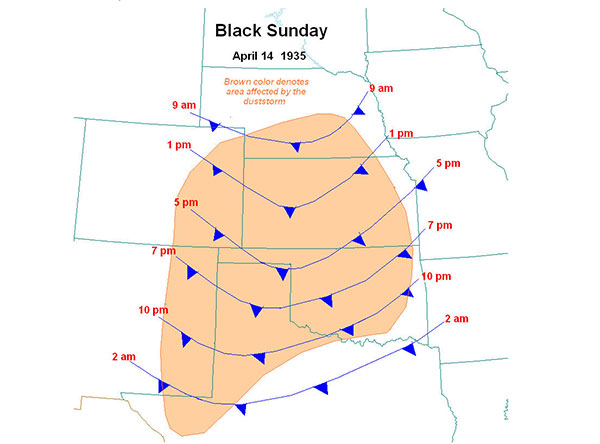

By the spring of 1935, the residents of the High Plains— a subregion on the western edge of the Great Plains— had already lived through years of dust and despair. But for many, the worst day of the Dust Bowl came that year on the afternoon of April 14th. At 2:49pm, a massive mountain of dust ahead of a mid-spring cold front raced into the High Plains from central Nebraska at a rate between 50-60 mph. At around 4:00pm, the storm slammed into the Oklahoma Panhandle and far northwestern Oklahoma, with winds topping 40 mph. As it surged south and southeast that evening, the dust storm blackened the skies across much of the region, covering an area of about 800 miles by the time it reached the Mexican border the following morning. The Oklahoma and Texas Panhandles were hit hardest as wind speeds exceeded 60 mph and the dust became so thick that visibility vanished entirely (2). Dodge City, Kansas recorded the storm’s arrival at approximately 3:00pm with a temperature of 84℉, which quickly plunged into the 50s as the cold front moved through, bringing northerly winds up to 30 mph and near-zero visibility. Just before 7:00pm, the storm barreled into Amarillo, Texas driven by 50 mph winds that cloaked the city in a thick layer of dust (2).

with a shaded region to visualize the area affected by the dust storm, NOAA NWS.

Now known as Black Sunday, this storm wasn’t just terrifying— it turned deadly. The National Weather Service (formerly the Weather Bureau) called it “a storm of terror,” claiming it was the worst storm to occur in this region at the time (1). Many animals, both wild and domesticated, perished in the Black Sunday dust storm. Due to Pneumoconiosis (i.e., “dust pneumonia”) and suffocation, around 20 people in Kansas lost their lives from this event, while thousands suffered the loss of their homes and livelihoods, contributing to the estimated half a million people who were left homeless and destitute by the combined forces of both the Dust Bowl era and the Great Depression (3, 2).

This particular storm became a defining symbol of the Dust Bowl, a term that appeared in the press for the first time the very next day when Associated Press reporter Robert E. Geiger used it in his coverage from Boise City, Oklahoma (1). While the Dust Bowl affected the western Plains most severely, the crisis had a far greater reach, both physically and politically: dust from the Plains reached Washington, D.C. on more than one occasion, and less than two weeks after Black Sunday, Congress passed the Soil Conservation Act of 1935 (1). This legislation sought to address, and reverse, many of the farming practices that had rendered the Plains far too vulnerable to wind erosion.

Final Thoughts

Black Sunday left a lasting mark on the nation’s conscience. In the storm’s wake came a recognition that our relationship with the land is never one-sided, and that short-term gain can lead to long-term collapse when natural ecologies are drastically changed or wishfully ignored.

The American West has experienced recurring drought for as long as it’s been inhabited by people, and we ignore this fact at our own peril when we build cities or plant farms to the horizon under the assumption that the benevolent conditions we’ve come to expect will continue. We were reminded of this during the Dust Bowl and we are being reminded again as the Colorado River and lakes and reservoirs across the West shrivel beneath another drought that was not foreseen or considered when water rights were allocated, crops were planted, and cities expanded (7, 8). However, unlike during the Dust Bowl, anthropogenetic (human-caused) climate change has exacerbated the current drought in the West. Recent research has found that hotter temperatures, rather than reduced precipitation, have been the largest driver of drought severity since 2000 (9). This human influence – this “push” on the system – plays out atop the natural variability of drought in the American West.

The Dust Bowl in the 1930s, like water scarcity in the West today, was not simply a natural disaster, but a man-made one that exposed how easily abundance can give way to collapse when we treat natural resources as endless and fail to understand our impact on the systems with which we interact. While land-use and farming knowledge and practices have significantly improved over the last century, Black Sunday stands as a grisly warning from the past that conversations around climate resilience and sustainable land-use should continue to push policymakers, farmers, and communities alike to keep asking hard questions and making scientifically-informed choices.

References

- “The Black Sunday Dust Storm…” NOAA NWS

- “88th Anniversary of April 1935…” NOAA NWS

- “Pneumoconiosis” John Hopkins Medicine

- Figure 1, by George Everett Marsh Jr., Wikimedia Commons

- Figure 2, “88th Anniversary of April 1935… NOAA NWS

- “The Dust Bowl: A Film by Ken Burns,” Florentine Films and WETA-TV, November 2012.

- “Drought in the Colorado River Basin: Insights using open data,” United States Geological Survey.

- “The Colorado River crisis: Water shortages, climate change, and sustainable management,” Penn State Institute of Energy and the Environment, 19 March 2025.

- “Study: heat, not lack of precipitation, is driving western U.S. droughts,” NOAA Research, 8 November 2024.