Could a Hurricane Make Landfall in Southern California?

Published: August 11th, 2023

Hurricane season is well underway in both the North Atlantic and Eastern North Pacific ocean basins which officially started June 1 and May 15, respectively, with both ending November 30. These dates are based on past climatology in each basin, although hurricanes have been observed before and after these season dates. While many are more familiar with the hazards associated with landfalling hurricanes in the southeastern region of the United States, the question recently came up, could a hurricane make landfall in southern California? Longtime residents of southern California and the southwestern region of the United States are familiar with occasional heavy rainfall downstream of a tropical cyclone or tropical cyclone remnants during the later summer or autumn months, the last being from Tropical Storm Kay in early September of 2022. But what’s keeping these tropical cyclones from maintaining enough strength to make landfall as a hurricane further north? Has it been observed, and could it happen in southern California?

This article isn’t meant to be an exhaustive lesson on hurricanes, but it is worthwhile to give some background information. First, the term tropical cyclone is used here to represent both tropical depressions, storms and hurricanes. Other areas of the world use different naming for hurricanes, such as typhoons in the Western North Pacific ocean basin. Next, it is helpful to provide brief context on the conditions needed for the formation, intensification, and weakening of tropical cyclones.

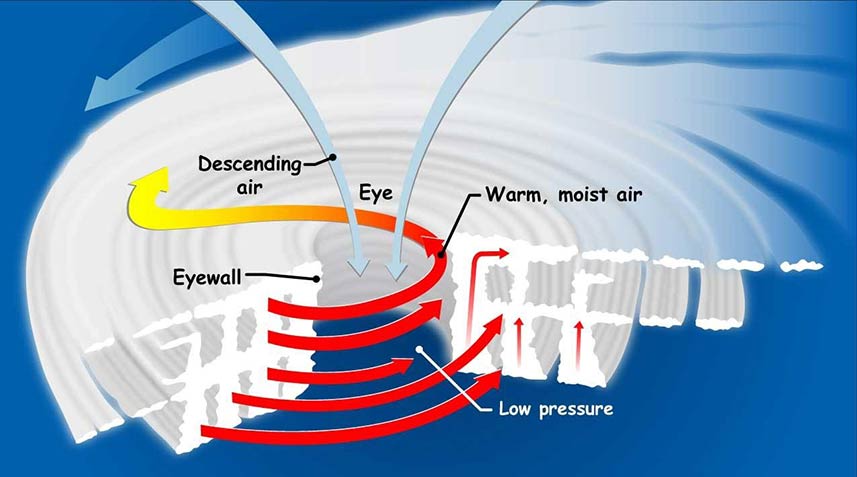

The first ingredient for a tropical cyclone is some disturbance in the atmosphere - a local area of higher moisture or lower pressure - that usually originates over land such as central Africa or Central America for the Western Atlantic and Eastern North Pacific basins, respectively. Next, the disturbance needs fuel in the form of warm ocean waters and moisture, along with upper level conditions to support the development of individual storms in and around the disturbance. Last, but certainly not least is the absence of wind shear - that is, little to no change in wind direction or magnitude with height through the atmosphere (troposphere). All of this allows the growth and organization of storms in and around the disturbance. Large amounts of heat produced aloft by the convective storms, due to a process called latent heat release, results in lower pressure near the ocean surface. This increases the intensity of winds moving inward (from higher to lower pressure) which along with what’s called the Coriolis force (due to earth’s rotation) results in counter-clockwise winds that characterize cyclones in the Northern Hemisphere (opposite direction in the Southern Hemisphere). This circulation helps to draw in and centralize more energy while rising air eventually spreads outwards at the top of the tropical cyclone. A schematic diagram of an organized tropical cyclone is shown in figure 1 (https://gpm.nasa.gov/education/articles/how-do-hurricanes-form). Tropical cyclones begin to weaken as they encounter dry air, cooler ocean surface water, or wind shear. Additional information can be found at the National Hurricane Center (https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/outreach).

Click images for larger views.

Tropical cyclones in the Eastern North Pacific ocean basin tend to form off of the southern Mexico coast and are directed, or steered, westward by easterly winds. Some tropical cyclones continue a westward track into the Central Pacific while others move northward due to variations in steering winds and interactions with other storm systems associated with the jet stream to the north. It is these northward turning tropical cyclones that can on rare occasions move close to the southwestern United States. Colder ocean surface temperatures off the California and Baja California coast often lead to weakening of tropical cyclones before reaching the southwest U.S.

The occurrence of tropical cyclones and their effects in and near southern California, and more broadly the southwest U.S., has been most notably summarized in two studies. The first is Chenoweth & Landsea (2004) who mention four occurrences of tropical storm force winds being measured in Arizona or California dating back to 1939, with all occurring in September or October. The last occurrence was Tropical Storm Nora in late September 1997 which made landfall in Baja California as a category 1 hurricane but was able to maintain tropical storm intensity while moving north over Yuma, Arizona before further weakening.

The authors of this study primarily focused on a storm that impacted a corridor from San Diego to Los Angeles on October 2, 1858. They provide various evidence of wind speed and wind damage reports equivalent to a category 1 hurricane across the San Diego area on this day. Note that it’s not known whether this hurricane actually made landfall in California, as the authors suspect the hurricane weakened and turned northwest, remaining just offshore of the California coast. Details of flooding and damage are not summarized here but can be found in the article. It is worth sharing that Chenoweth & Landsea (2004) suggest that a direct category 1 hurricane landfall in Los Angeles or San Diego would now result in hundreds of million in damages, as estimated in 2004.

The second study, focusing on the impacts of tropical cyclones in the southwest U.S. is Smith (1986), which goes into deeper detail on past tropical cyclones as well as heavy rain events from remnant moisture of East North Pacific tropical cyclones. This article was written before the discovery and summary of the 1858 San Diego hurricane, which was not discussed. The article did, however, mention the possibility of a weak hurricane making landfall in southern California or near Yuma, Arizona (as almost happened with Hurricane Nora in 1997) if ocean surface temperatures were about 24 degrees Celsius or greater off of the California and Baja California coasts, and the hurricane was moving sufficiently fast to the north and east to maintain sufficient intensity.

As it relates to sea surface temperatures (SSTs) we would expect that warmer than usual SSTs across and near coastal California and Baja California would support a landfalling tropical cyclone. Chenoweth and Landsea (2004) provide evidence and citations showing some tendency of tropical cyclones moving into the southwest U.S. occurring during El Nino or positive El Nino/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) years. El Nino conditions are observed when ocean temperatures across the eastern equatorial Pacific are warmer than average, which typically corresponds to warmer SSTs further north in the East North Pacific ocean.

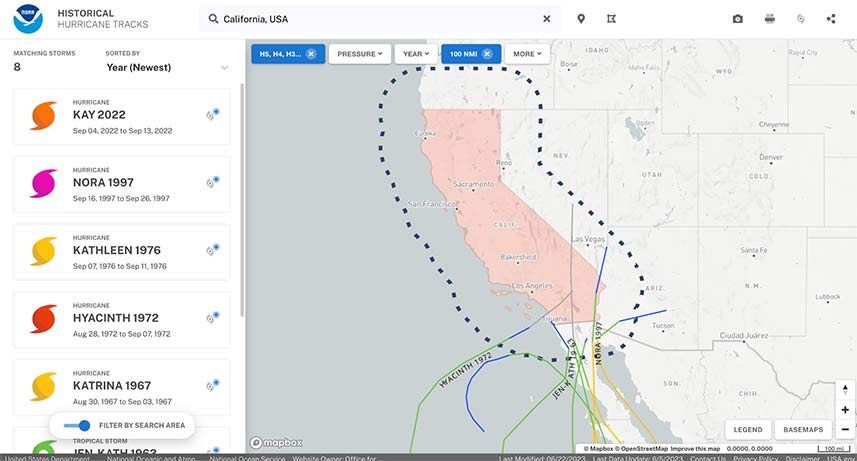

A less stringent threshold looking at any tropical cyclone with tropical storm or greater intensity moving within 100 nautical miles of California reveals eight tropical cyclones since 1951 (figure 2; https://coast.noaa.gov/hurricanes). Five of these tropical cyclones occurred during El Nino years while two occurred during neutral ENSO conditions. Tropical Storm Kay was an exception, occurring during La Nina conditions in 2022.

Current SSTs and anomalies are shown in figure 3; https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/ product/5km/index_5km_ssta.php, indicating that while areas of the East North Pacific are warmer than average, there are portions cooler than average, most notably in a corridor from California to Hawaii. While much of this area has shown warming over the last 7 days, cooling has been seen off of the southern California coast. So while we are in positive ENSO (El Nino conditions), current SSTs off of California and the northern Baja California coasts suggest a decreased probability of a tropical cyclone making it to or near southern California in the near future. But note, past tropical cyclones making this far north have happened in September and October, so if continued and more expansive warming is seen, this could favor tropical cyclones reaching further north later this season. Remember also that other factors such as wind shear play a large role in tropical cyclones as they move more north.

So what can we say about the possibility of a tropical storm or even a hurricane making landfall in southern California?

Evidence points to multiple tropical storms and one hurricane making landfall in recorded history. This alone suggests that it’s only a matter of time; however, how much time remains is an open question. A weak hurricane could make landfall in southern California this season, or we could be waiting another century. When it does happen though, past cases reveal it would most likely occur in September or October.

The relatively low occurrence rate of tropical cyclones impacting southern California makes it difficult to fully understand the impacts and hazards, particularly with the robust urbanization and growth along and near coastal stretches of southern California. While the intensity of any hurricane will be relatively weak compared to those sometimes seen in the Western Atlantic ocean basin, the impacts could be severe and warrant consideration and planning among managers and developers of infrastructure and public safety across southern California.